February 19, 2026 by Mike Powell

When birds are perched in the trees during the winter, you often do not have a sense of their environment when you look at photos of them. Some sparrow species, however, like to poke about on the ground and when I manage to capture some shots of them, you get much better sense of the harshness of their environment, as was the case with this White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) last week at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

White-throated Sparrow overwinter with us, but disappear during the warmer months when they fly north to breed. One of my favorite identification features for this species is the bright yellow stripe in their lores (the area between their eyes and their bills). This particular sparrow was feverishly poking about in the snow as if foraged for food and I was particularly pleased when it hopped up onto a log and gave me a chance to capture an unobstructed shot of it.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, sparrow, Tamron 150-600mm, white-throated sparrow, Woodbridge VA, Zonotrichia albicollis | 2 Comments »

February 17, 2026 by Mike Powell

This Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) was facing away from me when I first spotted it last week at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, but I waited patiently for it to move its head and was rewarded with this profile pose. Of course, my challenge was to capture the moment, and I was happy that I was able to get an unobstructed shot of the little bird.

You have to be out there to have opportunities like this and a combination of skill and luck (and quick reactions) to get the shot. As I learned long ago when I was a Boy Scout, it is important to “Be Prepared.”

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Melospiza melodia, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, song sparrow, sparrow, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 3 Comments »

February 16, 2026 by Mike Powell

I was thrilled to spot this Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) last week at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Unlike Great Egrets (Ardea alba) that migrate out of our area in the fall, Great Blue Herons remain with us throughout the entire year. A lot of the water at the wildlife refuge was frozen, but this heron managed to find an open stretch of water and was fishing at the side of what might be a beaver den.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Ardea herodias, Canon 7D, Great Blue Heron, heron, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | Leave a Comment »

February 14, 2026 by Mike Powell

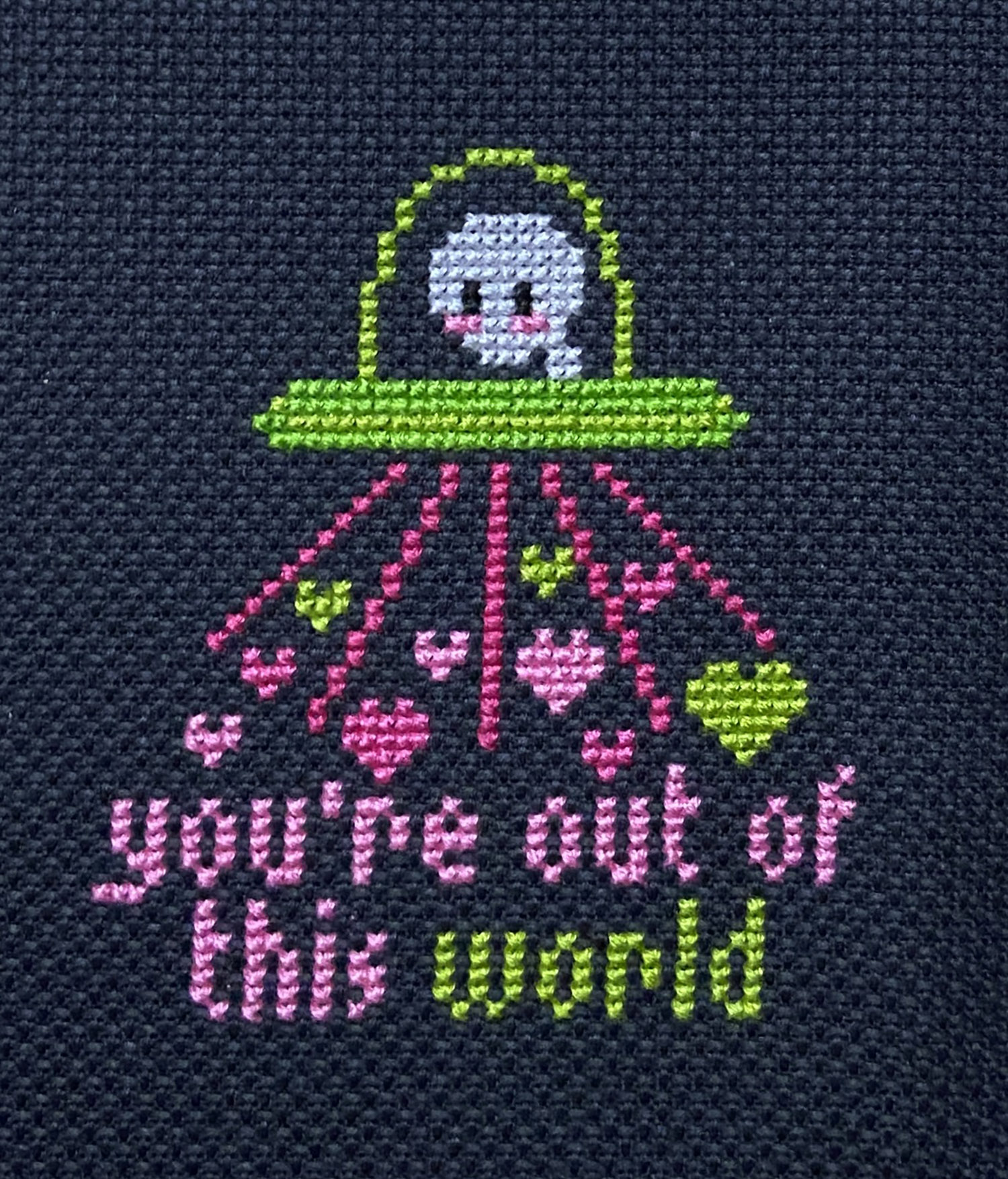

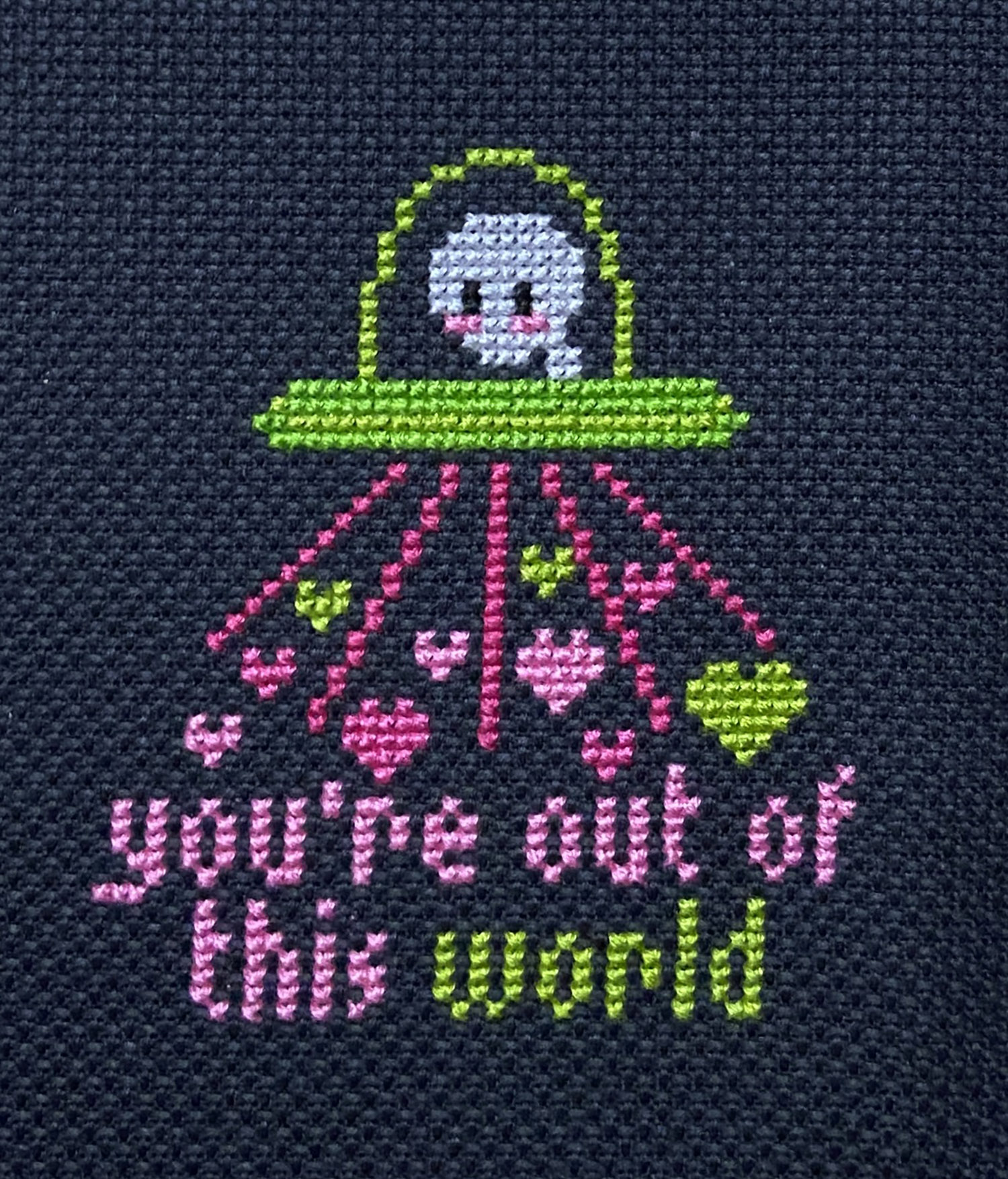

Are you a traditionalist when it comes to celebrating Valentine’s Day or do you prefer a more modern approach? The cross stitch community is amazingly diverse in approaching this holiday.

Here are two projects that I have recently stitched. Love Lives Here by Michelle @bendystitchydesigns.com is traditional in its colors and motifs, while Out of This World by DH @www.etsy.com/shop/TheCozyDHShop has a modern vibe in its colors and subject matter.

I loved stitching them both!

Happy Valentine’s Day, no matter how you choose to celebrate.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in cross stitch, Photography | Tagged bendystitchydesigns, counted cross stitch, cross stitch, love lives here, Out of this world, TheCozyDH, Valentine's Day, Valentine's Day 2026 | 6 Comments »

February 13, 2026 by Mike Powell

When I am lucky enough to spot warblers, it is usually in the spring and autumn, when they are migrating through Northern Virginia where I live. One exception is the Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata) that stays here for much of the winter.

I was delighted to get a glimpse of this Yellow-rumped Warbler on Wednesday at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge and even more thrilled that I was able to capture a couple of shots of the handsome little bird. The warbler was feverishly foraging and was rather hyperactive. The challenge for me and my camera was to acquire the subject in my viewfinder as soon as I saw it and then to accurately focus on it before it flew to a new perch.

On this day, I more or less met the challenge with this warbler, but like all other wildlife photographers, I have plenty of stories of “the one that got away.”

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Photography, Birds, Nature, wildlife, Winter, warbler | Tagged Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Setophaga coronata, Tamron 150-600mm, warbler, Woodbridge VA, Yellow-rumped Warbler | 4 Comments »

February 12, 2026 by Mike Powell

An American Coot (Fulica americana) turned its head as it swam away from me yesterday at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, allowing the light to illuminate its stunning red eyes that often remain hidden in the shadows.

This was the first time that I have been out with my camera in several weeks. I have been mostly housebound during that time, due to the frigid temperatures and lingering snow that has made driving a challenge. Here in Northern Virginia we are not used to dealing with this much snow and the only now are we starting to warm enough for the snow to start to melt.

Yesterday was warm enough that the icy top layer of the snow had softened enough that it was no longer slippery, but it also mean that I was sinking into the snow several inches as I trudged along the still snow-covered trails at the wildlife refuge.

I was happy to have a few encounters with birds and I’ll share some more photos in the next few days, but thought I’d get back to more regular postings, now that I have something to share.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged American Coot, Canon 7D, coot, Fulica americana, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 1 Comment »

January 20, 2026 by Mike Powell

When I spotted this Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) last week, it was perched uprignt in a tree at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Suddenly it seemed to develop an itch that absolutely had to be scratched. The heron carefully balanced itself on one leg, bent its head down, and scratched away with its long nails.

Sometimes life is like that and you just have to scratch that itch immediately. Trust me, I’ve been there.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Ardea herodias, Canon 7D, Great Blue Heron, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, scratching an itch, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 4 Comments »

January 16, 2026 by Mike Powell

I have not been very good in forcing myself to get out early on the cold winter mornings of January so far this year. However, I did visit Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge one cool, misty morning earlier this month.

The weather conditions created a moody, atmospheric vibe that prompted me to take some rather minimalist landscape shots. The two photos that I have included in this post more or less speak for themselves. You can see what the subjects are, but they are much less important than in my usual photos—I was focused more on capturing the mood rather than the theoretical subjects.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Art, Landscape, Nature, Photography, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, foggy morning, misty morning, morning fog, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 2 Comments »

January 8, 2026 by Mike Powell

Some birds cooperate when I try to photograph them by posing, but often they fly away as soon as they detect my presence. Most often that results in a butt shot, which is not exactly the most flattering view of a bird (or a person for that matter).

Sometimes though, I get lucky and get an interesting shot of the bird as it is moving out of view. This past Monday at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, I captured some shots of a departing Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) that really showcased its impressively wide wingspan. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the wingspans of Great Blue Herons are about 5.5-6.6 feet (1.7-2.0 meters), an amazing size for a bird that weighs only about 5 pounds (2.3 kg).

I was zoomed in with my telephoto lens when the heron took off unexpectedly. As you can see in the first photo, I reacted a bit too slowly and was not quite ready when the heron extended its wings and jumped out of the water. The second shot shows the heron’s fully extended wings as it flew low over the pond before gaining some altitude (an I managed to capture the full wingspan). In the final shot, you can finally get a glimpse of the heron’s head and it has lifted its legs up against its body into more aerodynamic flight position.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Ardea herodias, Canon 7D, Great Blue Heron, heron, heron takeoff, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 7 Comments »

January 7, 2026 by Mike Powell

I photographed this little Carolina Wren (Thryothorus ludovicianus) and this spherical Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) yesterday during a lengthy trek through Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. The weather yesterday was cold and overcast, which mean that the conditions were less than ideal, but I was feeling a bit of cabin fever and was happy to be outdoors for my first photo trek of the new year.

I could hear a lot of birds singing in the trees and rustling about in the underbrush, but did not get very many clear views of them. Still, I was happy with the results that I achieved. I snapped off the first photo when the wren momentarily hopped up from the leaves in which it had been foraging and looked in my direction.

The sparrow in the second photo was a bit more in the open, but its head was most often turned away from me. I really like the way that the bird’s markings were an almost perfect match for the colors and the patterns in the background.

It felt good to be out with my camera and to experience the tranquility of nature that so often soothes my soul.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Carolina Wren, Melospiza melodia, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, song sparrow, Tamron 150-600mm, Thryothorus ludovicianus, Woodbridge VA | 5 Comments »

January 2, 2026 by Mike Powell

It’s hard to believe that a new year has already started. Where did 2025 go? I had to really pay attention when I wrote the date on my first check of 2026 this morning—yes, I still write a few paper checks each month, though I am moving increasingly to paying most of my bills on line.

For a variety of reasons, I kind of backed off from photography a bit this past year. According to the stats portion of WordPress, I published 196 posts in 2025 for a total of over 34 thousand words. That may seem like a lot, but over the lifetime of this blog, I’ve probably averaged about 400 postings a year, with a high of 653 posts with a total of just under 100 thousand words in 2014. In case you are a stats nerd, my lifetime totals since my start in 2012 are 5502 postings with a total of 581988 views.

Strangely enough, the number of views in 2025 was an all-time high of over 89 thousand. Why? I think that the addition of an AI summary to Google searches may have brought forward a number of my posts to a broader audience and a sharp increase in the number of viewers from China (over 12 thousand views in 2025) may reflect the activity of bots or some other web tools.

I haven’t given up on wildlife photography, but during the second half of 2025 I averaged going out with my camera only about once a week. In late December I captured this image of a Cedar Waxwing bird (Bombycilla cedrorum) that was most hidden in the shadows. I was thrilled to be able to capture the distinctive crest of this really cool bird.

During this past year I have rediscovered my love of counted cross stitch and have devoted a substantial amount of my “extra” time to stitching. It’s a strange mix of hobbies to have one that is active and outdoors and another that is mostly sedentary. The second photo shows a recently completed project called Festive Cardinal, designed by Max Pigeon of Pigeon Coop Designs. I showed this project a while back when it was almost completed, but thought it would be fun to show it again in its finished form, because it shows the way that my photography interests and cross stitch interests overlap in terms of subject matter.

So what will 2026 hold for me? I really don’t do new year’s resolutions and am not much for planning—I came across a joke yesterday that new year’s resolutions are things that go in one year and out the other. Sorry. I’m hoping that I’ll achieve a better balance between these two primary hobbies, but I may go off on tangents with watercolor painting, knitting, or even sewing—maybe I’ll finally learn to use the sewing machine that a friend gave to me. I guess that the one thing that ties all of these interests together is a sense of wonder and curiosity and a desire to tap into a sense of creativity that was mostly suppressed during my working career.

Best wishes for a happy and healthy new year. Technically I am also wishing those of you who celebrate Christmas a Merry Christmas, because today is only the ninth day of Christmas (on which the well-known song indicates that my true love gave me nine ladies dancing).

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, cross stitch, Nature, Photography, Winter | Tagged @pigeoncoopdesigns.com, Bombycilla cedrorum, Canon 7D, Cedar Waxwing, Festive Cardinal, Max Pigeon, New Year 2026, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Pigeon Coop Designs, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 15 Comments »

December 29, 2025 by Mike Powell

Many different warblers pass through my area during the spring and the autumn, but the Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata) is one of the few species that remains here for most of the winter. Their colors are pretty subdued during the winter season, but they do have small patches of bright yellow on their sides and on their rump. It is always a delight to spot their flashes of yellow as they forage in the trees.

I captured this shot of a Yellow-rumped Warbler in mid-December as it was peeking out from behind a tree at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Setophaga coronata, Tamron 150-600mm, warbler, Woodbridge VA, Yellow-rumped Warbler | Leave a Comment »

December 27, 2025 by Mike Powell

When I am out in the wild with my camera, most of my senses are fully engaged. I am listening intently and scanning constantly, seeking audio or visual clues of the presence of potential subjects. During much of the year, sounds don’t help much, because the leaves on the trees hide the sources of the sounds. I marvel at the ability of some folks to identify birds by their calls, but I can do that with only a handful of species. So most of the time I rely on movement and to a lesser extent on color for me to acquire a target—if a bird (or insect) remains still, it often will remain invisible to me.

Last week when I was walking about at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, I heard the gentle tapping sounds of a woodpecker. I looked in the general direction of the sounds and saw a distant snag, but did not see the woodpecker. Did I have the right tree identified? As I was focusing on the tree, a Red-bellied Woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) poked its head out from behind the tree and I quickly snapped off a couple of photos before the bird disappeared again from view.

The woodpecker was pretty far away, even for my telephoto zoom lens, so I knew that I did not get the kind of close-up detailed image that I usually like to capture. However, when I was reviewing the photos on my computer, I found myself drawn to this profile shot of the woodpecker, surrounded by the wonderful texture of the lichen-covered bark of the tree. The image has a bit of an artsy, minimalist feel that I really like.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Art, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Melanerpes carolinus, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Tamron 150-600mm, Tamron 150-600mm telephoto, Woodbridge VA, woodpecker | 8 Comments »

December 26, 2025 by Mike Powell

When the leaves are gone from the trees, it’s a little easier to spot perched Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), like this one that I photographed last week at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. I am blessed to live in an area where there are enough bald eagles that it is not uncommon for me to spot one. However, the eagles have much more developed senses that I do, so often my first indication of their presence is when they are flying away from me, as you can see in the first photo below.

In the case of the second photo, there was a good deal of vegetation between me and the eagle that partially hid my presence. I was able to manually focus my lens on the perched eagle through the vegetation and get a relatively clear shot of the eagle, which took off almost immediately after I had snapped a couple of photos.

I am not certain if I will be able to get out with my camera during the few remaining days of 2025, so these photos may well be my last shots of the year of these majestic birds.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Bald Eagle, bald eagle takeoff, Canon 7D, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 4 Comments »

December 25, 2025 by Mike Powell

I realize that not everyone celebrates Christmas, but I wish the best for all of you during this holiday season. In the midst of all of the hype and activity surrounding this overly commercialized day, I hope that you can rediscover its simple message of joy and hope.

On Christmas Day, I can’t help but think of the final verse of “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” which reaffirms that hope: “Then pealed the bells more loud and deep. God is not dead nor doth he sleep. The wrong shall fail, the right prevail, with peace on earth, good will to men.”

The first photo below shows my almost completed cross stitch project Festive Cardinal designed by Max Pigeon of Pigeon Coop Designs. The second photo shows the inside of my church, St. Martin de Porres Episcopal Church, during the afternoon of Christmas Eve, when we were practicing the music for the evening service. I tear up a little remembering the congregation in the darkened sanctuary singing Silent Night by candlelight at the Christmas Eve service last night—it is always one of the highlights of Christmas for me.

Merry Christmas to all of you.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Christmas, counted cross stitch, cross stitch, Photography, Winter | Tagged @pigeoncoopdesigns.com, Christmas, Christmas 2025, Festive Cardinal, Max Pigeon, Merry Christmas, Pigeon Coop Designs, St Martin de Porres, St Martin de Porres Episcopal Church | 15 Comments »

December 24, 2025 by Mike Powell

Last week at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge I spotted a small group of American Robins (Turdus migratorius) clustered around a large puddle. Some of the birds took their turns drinking from the puddle, while others took advantage of the opportunity to take a bath. Some of the birds merely flapped about a bit in the water, but the robin in the photo below seemed to enjoy soaking in the cold water.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged American robin, bathing robin, Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, robin, Tamron 150-600mm, Turdus migratorius, Woodbridge VA | 3 Comments »

December 22, 2025 by Mike Powell

Some birds, like Great Egrets and Green Herons, leave our area during the cold months to overwinter in warmer places. Great Blue Herons, however, remain with us throughout the year. I imagine that it is tough for them to find food, especially when the small ponds where I often spot them are frozen over.

I was happy last week to spot this Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. There was ice on parts of the pond where the heron was standing, but there were still some open areas. I watched as the heron patiently scanned the water for potential prey and captured this shot as the heron was pulling a small fish out of the water.

It’s a really small fish and I encourage you to click on the image to enlarge it and get a better look at the fish. For the heron, the fish is probably only an appetizer, but at this time of year, food is scarce, so even tiny bits are undoubtedly welcome.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Ardea herodias, Canon 7D, Great Blue Heron, Great Blue Heron fishing, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 2 Comments »

December 20, 2025 by Mike Powell

I was thrilled on 18 December to capture this shot of a beautiful little Field Sparrow (Spizella pusilla) during a visit to Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. I initially heard this bird as it was foraging in the underbrush and was searching for it when it unexpectedly hopped up onto a fallen branch. The little sparrow posed momentarily for me and I was able to capture this cool little portrait of it. Even though the background is pretty cluttered, the sparrow really stands out in the shot.

When I took the photo, I was not able to identify the sparrow species. However, the rust colored crown, orange-pink bill, and white eye ring as quite distinctive, so I was able to find the Field Sparrow in my identification guide. Still I was not absolutely certain of my identification, so I posted a photo to a Facebook birding group and several experts there confirmed that it was indeed a Field Sparrow.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Field Sparrow, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, sparrow, Spizella pusilla, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 6 Comments »

December 19, 2025 by Mike Powell

Although the weather was a bit warmer yesterday (18 December), there was still plenty of ice in the frigid waters off of the shores of Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. For many of us here in the United States, winter does not officially begin until this Sunday, the 21st of December, but we have already had two snow storms with measurable accumulation and some periods of sub-freezing temperatures.

With rain in the forecast for the following couple of days, I ventured out yesterday to my favorite local wildlife refuge with my camera, looking primarily for birds.I did not have a huge amount of success in capturing images of these birds, but it was enjoyable nonetheless to be outdoors in the relatively comfortable temperatures of a beautiful December day.

I was happy that I remembered to take some landscape style shots with my iPhone to document the day—when I am carrying around my camera with a long telephoto zoom lens, I often forget to take some wide-angle shots like these ones.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Landscape, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged frozen water, ice, iPhone 11, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Woodbridge VA | 1 Comment »

December 11, 2025 by Mike Powell

Now that I am focusing mostly on photographing birds rather than dragonflies or butterflies, I am having to reacquaint myself with my long telephoto lens (Tamron 150-600mm) and with the related differences in shooting techniques. During the warmer months, I spend most of my time looking downwards and scanning an area no more than 10 feet (3 meters) in front of me. When it comes to the colder months, I spend much more time looking upwards for bird activity, although some of the remaining birds forage on the ground, so I can’t totally forget to look down. I also scan areas that are much farther away from me, particularly because my long lens cannot focus on anything that is closer than 9 feet (2.7 meters) from me.

Last week I was delighted to spot this beautiful Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. I am gradually learning the differences in coloration in the various sparrows in our area, though I must confess that sparrow identification is an ongoing challenge for me.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Melospiza melodia, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, song sparrow, sparrow, Tamron 150-600mm telephoto, Woodbridge VA | Leave a Comment »

December 9, 2025 by Mike Powell

During the wintertime, when the leaves are gone from the trees, I have a better chance of spotting tiny birds, like this Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) that I photographed last week at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. It was sunny but cold when I photographed the chickadee. Like most birds that I encounter during the winter months, this chickadee looked almost round, having fluffed up its feathers in order to retain its body heat. I have the same body shape when I bundle up in my cold weather clothes and increasingly even without them.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Canon 7D, Carolina Chickadee, chickadee, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Poecile carolinensis, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 7 Comments »

December 5, 2025 by Mike Powell

I was delighted to spot this Autumn Meadowhawk dragonfly (Sympetrum vicinum) on Wednesday, 3 December, at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Despite our recent cold nights, many of which have dipped below the freezing level, this hardy dragonfly managed to survive.

It is snowing out right this moment, so I am not sure how much longer I will be seeing these beautiful little creatures, but I’ll almost certainly be out with my camera next week to see what I can find.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Dragonflies, dragonfly, Insects, Nature, Photography, wildlife, Winter | Tagged Autumn Meadowhawk, Autumn Meadowhawk dragonfly, Canon 7D, male Autumn Meadowhawk, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Sympetrum vicinum, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 7 Comments »

November 27, 2025 by Mike Powell

Happy Thanksgiving to all those celebrating this American holiday. Whether we are soaring high or resting at water’s edge, like this Bald Eagle couple (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), we are all blessed.

The Scriptures tell us we should “Rejoice always, pray continually, give thanks in all circumstances.” A recent sermon reminded me that we are called to give thanks “in” all circumstances, even when it may not be possible to feel thankful “for” all of them. It’s a matter of having what some have called an “attitude of gratitude.”

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Birds, Inspiration, Nature, Photography, Thanksgiving, wildlife | Tagged attitude of gratitude, Bald Eagle, Bald Eagle couple, Canon 7D, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Tamron 150-600mm, thanks, Thanksgiving 2025, Woodbridge VA | 4 Comments »

November 25, 2025 by Mike Powell

I haven’t yet checked this week, but these Autumn Meadowhawk dragonflies (Sympetrum vicinum) that I spotted on 17 November at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge are likely to be among the last dragonflies that I see this season.

Autumn Meadowhawks frequently perch flat on the ground or on dried leaves on the ground. I was delighted when a male Autumn Meadowhawk perched almost vertically on a colorful fallen leaf and I was able to capture the first image below. By contrast, the female in the second photo chose a less interesting drab leaf on which to perch.

I’ll try to go out later this week to see if I can find some late season survivors, but it is becoming clear to me that this year’s dragonfly season is nearly over.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Dragonflies, dragonfly, Insects, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged Autumn 2025, Autumn Meadowhawk, Autumn Meadowhawk dragonfly, Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Sympetrum vicinum, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | Leave a Comment »

November 19, 2025 by Mike Powell

As I was walking along the trails at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge on Monday, I spotted a small flock of birds foraging high in the trees. When I zoomed in with my telephoto lens, I was delighted to see that they were Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis). It may be a bit trite and a bit of a cliché, but I really do love bluebirds—they make me happy.

As you can see from the photos, Eastern Bluebirds have a substantial amount of orange plumage in addition to their blue feathers. Years ago, one of my youngest viewers, Benjamin, suggested that they should be known as Orange Bluebirds and I chuckle as I remember that comment every time that I spot a bluebird.

It was a bit of a challenge capturing shots of these hyperactive little birds as they moved about in the colorful foliage, but I managed to get a few relatively decent shots. Ideally I would have liked for the bluebirds to have been at eye level, but I try to do my best with the conditions that I am given. That is the typical fate of a wildlife photographer.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged bluebird, Canon 7D, Eastern Bluebird, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Sialia sialis, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 5 Comments »

November 18, 2025 by Mike Powell

As we approach winter, birds in the wild have to work hard to find food. Yesterday I photographed this tiny Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, my local wildlife refuge as it worked to extract seeds from the spiky seed pods of a sweetgum tree.

Now that most of the insects are gone for the season, I have switched lenses on my camera. Although I usually have some additional lenses in my backpack when I am on my little photography expeditions, I generally tend to stick with the lens that is on my camera, During warmer months that tends to be a Tamron 18-400mm lens that has the flexibility to get wide angle shots in addition to close-up shots of insects, particularly dragonflies.

During the cold months, I use my Tamron 150-600mm lens, a longer telephoto zoom lens that gives me greater reach. This lens is quite heavy to hold for extended periods of time, so I normally use it with a monopod, as I was doing yesterday, to give me greater stability and hopefully sharper photos.

I am always amazed when I see chickadees hanging from these spiky seed balls. I realize that these birds don’t weigh much, but it’s hard to believe that they can hang from the same seed pod that they are working on.

I was thrilled to be able to capture this cool image of the chickadee in action, with the colorful foliage in the background giving it a real autumn vibe.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged Autumn Bird, Canon 7D, Carolina Chickadee, chickadee, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Poecile carolinensis, spiky gumballs, Sweet Gum, Tamron 150-600mm, Woodbridge VA | 10 Comments »

November 17, 2025 by Mike Powell

I am still doing a lot of cross stitching and thought that I would mix things up a bit today by featuring two projects that I have recently completed that feature cardinals, one of my favorite birds. I have not figured out how/if I will frame the pieces, but figured it might be interesting to show you the variety of styles that attract me.

The first photo shows a piece called “Autumn Bird” that was designed by Jody Rice at Satsuma Street. Jody’s style is associated with modern cross stitching with its use of bold colors that are not necessarily related to the colors that you actually see in nature. You won’t, for example, see colorful autumn leaves that look like the ones that I stitched.

The second photo shows “Quirky Quaker Cardinal” by Darling and Whimsy Designs and is more reflective of traditional cross stitching, with its use of a limited palette of muted colors and traditional motifs. I love the simplicity of this approach and this project was a fun and easy stitch for me.

The world of counted cross stitch has changed a lot in recent decades, and many people now use digital patterns and software to display their patterns as they are stitching. I’m a bit of a traditionalist and like to use the paper patterns that I can purchase at my local cross stitch store. For the moment at least, these two approaches happily co-exist.

In many ways, the “modern vs. traditional” debate in cross stitch is similar to the range of approaches that exist for wildlife photography. I happily continue to use a digital single lens reflex camera with its mirror and optical viewfinder and am not quite ready to embrace the more modern mirrorless camera, with digital viewfinders and built-in image processors.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Art, Birds, counted cross stitch, Nature | Tagged @darlingandwhimsydesigns, @satsumastreet, Autumn Bird, counted cross stitch, Darling and Whimsy Designs, Jody Rice, Northern cardinal, Quirky Quaker Cardinal, Satsuma Street | 2 Comments »

November 14, 2025 by Mike Powell

As I was walking along one of the trails at Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge this past Monday (10 November) I saw and heard a group of small birds moving about in the vegetation. Many of them flew away immediately, but a few of them remained in place a little while longer. I thought I recognized the prominent pattern as belonging to an American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis). I tracked one of the birds and captured the second shot, which confirmed my initial identification.

When I started to review my photos on my computer, I noticed that there was a second bird in the first photo below that I had not noticed when I took the photo. I naively assumed it must be another goldfinch. I posted the photo to a Facebook birding group and one of the more experienced birders there pointed out that the bill on the bird on the right was completely different. He identified the bird as an Orange-crowned Warbler (Leiothlypis celata), a species that he noted was “hard to find.” After reading that comment, I looked over my photos once again and decided to post the final photo of the warbler in a slightly different pose.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged American Goldfinch, Canon 7D, Leiothlypis celata, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Orange-crowned Warbler, Spinus tristis, Tamron 18-400mm, Woodbridge VA | 3 Comments »

November 13, 2025 by Mike Powell

I think that we may well be down to our last surviving dragonfly species. On 10 November I ventured out to Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge to look for any remaining dragonflies or butterflies. I did not find any butterflies, but was delighted to spot close to a dozen Autumn Meadowhawk dragonflies (Sympetrum vicinum).

Our temperatures this past week have dropped down close to the freezing level, which most dragonflies cannot tolerate. Autumn Meadowhawks, however, are hardy enough to survive a few light frosts as long as daytime temperatures remain relatively warm and sunny. Once we start receiving a few heavy frosts the remaining population starts to die off.

I was happy to capture some photos of Autumn Meadowhawks as they perched on the colorful leaves that litter many of the trails at the wildlife refuge. The dragonflies appeared to be content to remain in place soaking up the warmth of the sun as I approached and some even posed for me.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Dragonflies, dragonfly, Insects, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged Autumn 2025, Autumn Meadowhawk, Autumn Meadowhawk dragonfly, Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Sympetrum vicinum, Tamron 18-400mm, Woodbridge VA | Leave a Comment »

November 12, 2025 by Mike Powell

This past Monday (10 November) I was delighted to spot my first White-throated Sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis) of the season. White-throated Sparrows overwinter in my area of Northern Virginia and seem to have arrived fairly recently.

I love the distinctive markings of these little birds, with their white “beards” that remind me of Santa Claus and their bright yellow lores, i.e. the region between the eye and the bill. They are the only species of sparrows that I can reliably identify—for other sparrows I have to look closely at guide books in order to guess their species.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged Canon 7D, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, sparrow, Tamron 18-400mm, white-throated sparrow, Woodbridge VA, Zonotrichia albicollis | 1 Comment »

November 11, 2025 by Mike Powell

Sometimes it pays to be lucky (and persistent). Yesterday I visited Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge for this first time in over a week. It was cool (about 45 degrees (7 degrees C) and breezy, so I knew that my focus would be primarily on birds rather than insects.

Midway through the morning, I spotted a bird moving about high in the trees and I tried to track it. Eventually I realized that it was a Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa), one of the smallest birds in our area at only about 3-4 inches in length (8-11 cm). Golden-crowned Kinglets are skittish and do not stay still for very long, so I frantically tried to track this bird as it moved from branch to branch.

I took lots of photos, but in many of them the kinglet was partially hidden by the branches or was out of the frame. My favorite photo of the kinglet is the first one below. The kinglet paused for a moment and lifted it head, allowing me to get a little eye contact with the bird. As I was focusing in on the kinglet’s perch, the kinglet took off and I captured the second photo, a lucky midair shot. The final photo shows the kinglet in one of its many acrobatic poses that it used as it foraged for food.

In case some of you are curious, I did find a few dragonflies yesterday, but I’ll leave those photos for another blog post.

© Michael Q. Powell. All rights reserved.

Posted in Autumn, Birds, Nature, Photography, wildlife | Tagged Canon 7D, Golden-crowned Kinglet, kinglet, Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Regulus satrapa, Tamron 18-400mm, Woodbridge VA | 2 Comments »

Older Posts »